35 Years of Printing for the Gloucester Fishing Industry

April 1, 2025

By Randolph C. Carr

Commercial Street, 1980. ©Randolph C. Carr

In the Beginning

In February of 1971 I was released from high school on a work study program and began printing at Gordon College Press in Wenham as a general apprentice. It was exciting for me to have real work, and I quickly learned the basics of printing. By 1974 I was put in charge of the shop after my boss retired. The administration did not offer me the job, so I wanted to find another position in order to support my family. I was earning about $3.75 per hour when I left early in 1975.

I moved to Defiance Graphics in Rowley. In 1976 the country entered a recession and there was not enough work to keep me busy. I asked the owner if I could go out on the road and make cold calls to see if I could drum up some business. And keep me employed! I did get some new customers and a lot of valuable experience meeting prospects and selling printing.

The Fishing Industry in 1977

In 1977 I went to 33 Commercial Street in Gloucester as manager of the Curhan Company Printers. We served a variety of local businesses, but most of our work was for the fisheries. At the time, there were still many packers in Gloucester, including Atlantic Seafoods, Empire Fish, Frontiero Brothers, Mortillaro Lobster, New England Coast Seafoods, North Atlantic Fish, Ocean Crest Seafoods, and Star Fisheries. They packed fresh fish landed by the local fleet. The fish were then transported to wholesalers or retail stores. Time was of the essence in handling this fish.

The secondary processors were larger companies that processed frozen fish. Their product was caught and frozen at sea on factory ships, formed into blocks, packed in cartons, and palletized. The pallets of frozen fish blocks were trucked to companies like Gorton’s, Mass Coastal Seafoods, and O’Donnell-Usen Fisheries in Gloucester, or Caribou Foods, Channel Fish, Slade Gorton, Capeway Seafoods, and Frionor Seafoods in Boston or New Bedford. Because the product was frozen during transport and processing, time was not critical when handling this fish. The basic products that came out of the secondary processor’s plants included breaded cooked fish sticks, fish cakes, breaded cooked fish portions, or unbreaded raw fish portions. There were also many specialty products including scallops, shrimp, crab, lobster, and other prepared items.

In addition to the packers and secondary processors there were also smaller broker/dealers scattered around the North and South Shore. We did business with Universal Fish, Lewis Mills Seafood, Grotta Bay Seafood, Rainbow Seafoods, Dawnkist Seafoods, and Aquanor. These broker/dealers acted as middlemen between various counterparties in the industry.

Fish Labels

All these industry participants needed labels which Curhan printed and supplied. There were three basic types. The first type were lay-on labels (“outserts”) that were placed or glued on top of a paperboard carton containing the fish. Lay-on labels were used by the packers and processors to identify their brand. The label contained a description of the contents, the net weight, the specie, cooking or preparation instructions, and starting in the mid 1990’s, a bar code.

The second label type was for direct food contact (“inserts”). They were usually 3” x 2”, and carried the packer’s brand, and the specie. They were placed directly on top of a piece of fish. The ink and paper had to be approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration for “direct food contact.”

The third type of label was self adhesive. They were applied to inner boxes or shipping cartons and used a special adhesive that could withstand freezer storage. They were not something the average printer supplied.

Commercial Street pressroom, 1980. ©Randolph C. Carr

Overprinting Paperboard Boxes

Between 1975 and 1985 we also did a large volume of “overprinting” which involved running paperboard boxes through a modified offset press to change the specie. Gorton’s was the primary client for this work. This was heavy, hard work due to the weight of the flat cartons, Curhan’s uneven floors and the lack of facilities for pallet jacks or forklifts. The loading and unloading were done by hand with two wheelers. Coupled with the large quantities and short lead times involved, it was not easy work.

Early years

By 1979, there were five printers on Cape Ann. Curhan Printing, Cape Ann Ticket & Label, Chisholm & Hunt, and The Pressroom were all in Gloucester. Cricket Press was in Manchester. All five were doing sheetfed offset printing, with some letterpress work for special applications and finishing. Artwork was prepared using phototype paper galleys, pasted up mechanical art, film, and metal plates. During these early years at Curhan, in addition to managing the print production, I also took on the tasks of estimating jobs and billing completed orders. This helped me sell to new businesses like Varian Extrion who were moving into the Blackburn Industrial Park.

Maplewood Avenue buildout, 1980. ©Randolph C. Carr

Maplewood Avenue Move

In June of 1980 our landlord informed us that Curhan would have to move because of plans to renovate the Commercial Street Building. They gave us space at 33 Maplewood Avenue. Thus we undertook the expensive process of moving a printing company which required professional riggers for the equipment and contractors for the buildout at the new location. Moving is also disruptive, because fishery related work is time sensitive with very short lead times. With careful advanced planning we only had to shut down production for two work days. Long nights and several weekends were involved, but one of the best things that came out of the move was that we got a real loading dock, pallet jack, and flat interior floors, so material handling became much, much easier!

By 1981 business briefly settled into a steady routine. I managed the overall operations and finances while spending time on the road developing new business and delivering work. There was a lot of driving around.

Peak Years for the Fisheries

Meanwhile, the fisheries industry, while still a major player in the city’s economy, was beginning to show signs of stress. The Magnuson-Stevens Act had been passed in 1976 to extend U.S. territorial waters to 200 miles. This was supposed to keep foreign vessels out of U.S. waters. Unfortunately, it did very little to prevent overfishing because the U.S. fleet expanded to take advantage of the protectionist policy. 1980 was the peak of fish landings in Gloucester. By 1982 there was concern over declining fish stocks, along with talk of more government regulations on catch sizes and restrictions on the number of days at sea.[1]

Fishery Products International

Gloucester was not alone in feeling the effects of overfishing. The Canadian fisheries were also having problems. In 1982, the province of Newfoundland combined eight bankrupt fishing companies to form Fishery Products International, a quasi Crown corporation partly owned by the Canadian government.[2] Fishery Products would open a frozen fish processing facility in Danvers, Massachusetts and become Curhan’s largest account, a relationship which continued for many years.

During the 1980’s Fishery Products worked with Caribou Fisheries. I spent many Friday afternoons stuck in Boston’s rush hour traffic after delivering labels to Caribou’s Northern Avenue facility where they also produced onion rings. I will always remember walking through the processing plant enveloped by a haze of thick blue smoke from the fryers. When I got back in my car I smelled like a big cooked onion ring.

Buyout

In early 1982 founder Ed Curhan transferred ownership of the business to his son Serge. Ed then passed away in June. Serge was employed elsewhere and not involved in the activities of the printing company. At first, he left the operations and management to me. However, by late 1983 it was becoming evident that we disagreed about how the business should be run. In January of 1984 he informed me, over dinner, that I would be fired.

This was a shock, but I tried to stay calm and pointed out that without me, the business would fail. He had no interest in running the company, so I offered to buy him out. In January 1985 I became 51% owner of the company but unfortunately did not have the financial resources to manage the complete purchase by myself, and found it necessary to take a partner. We both took out second mortgages on our homes and structured a deal with the mortgage funds, a bank loan, and an agreement with Serge to take back part of the purchase price as a loan.

This was a turning point in my career because the full financial burden of the business was on me and my partner who managed production, while I concentrated on sales and finance. For several years we did work for the Federal Government, and had printing contracts for Pease Air Force Base, the U.S. Coast Guard, and other government agencies. We also did work for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and developed other commercial clients who were not fishery related. This helped, for a time, to reduce our concentration on the fisheries industry. But Fishery Products kept providing an ever larger share of our overall volume. As hard as I tried to diversify away from the fisheries, they just kept giving us more work.

2014 Birdseye building before demolition. ©Paul Cary Goldberg

Good Harbor Fillet

The trend accelerated when Good Harbor Fillet came to Gloucester. They started out at the Gloucester State Fish Pier and eventually moved to the old Birdseye plant on Commercial Street. The plant was built in the 1920’s by Clarence Birdseye to produce his newly patented frozen fish products.[3] We printed large volumes of Good Harbor’s labels and designed their first logo. It appeared on their early printed materials and was also painted on the tower of the Birdseye building. In 2014 the building was demolished to make way for a large tourist hotel... a harbinger of the “new Gloucester.”

1985 ... Technology Change and Demise of Fisheries Begins

But let’s return to 1985 when the first major wave of technological change started to sweep over the printing industry. Desktop computers and laser printers replaced earlier typesetting and mechanical art systems. We bought our first equipment in 1985. It was revolutionary. The artwork and typesetting was now prepared digitally.

All our energy was focused on sales, production, meeting the weekly payroll, and paying off our debt. I was constantly on the road trying to develop new business. The fisheries were still busy, although signs of stress continued to build, with regulations, competition, and continual price pressure on the processors. A difference of pennies per pound mattered in the seafood business, and this meant that our label pricing needed to be very competitive. Staying profitable was a constant challenge. In 1985 Pappas International Foods (Boston) and Capeway Seafoods (New Bedford) declared bankruptcy, and we wrote off bad debt from Seamark Seafoods.[4] Not the best way to start our first year of ownership.

Not Again!

Then, as we began 1986, our landlord told us we had to leave Maplewood Avenue. They wanted to turn the building into condos. Facing another expensive disruptive move, we purchased a 6,000 square foot building in Gloucester. Although we had already taken on substantial debt to finance the company buyout, we found ourselves back at the bank to ask for a real estate loan. Fortunately, our bankers thought we were a good credit risk, and so in the summer of 1986 we moved to 743 Western Avenue in Gloucester. As we had done only six years earlier, we worked long nights and weekends to keep the print production on schedule while managing the buildout and move. By the autumn of 1986 we were in our new building and getting settled in, again.

A Bit of a Slog

After we purchased the building, finished the buildout, moved, and got organized in our Western Avenue space, the next few years became a steady routine of printing, selling, and paying off debt. It was a bit of a slog. Our main fisheries clients still included Fishery Products, Mass Coastal Seafoods, Good Harbor Fillet, Universal Foods, National Fish and Seafood, a reorganized Capeway Seafoods, and Tichon. There was still a small amount of work coming from the local packers like Atlantic Seafoods and Empire Fish, but it was dwindling.

I was constantly trying to find new clients that were not fishery related, but rarely did the non-fisheries work ever exceed 35% of our overall sales. In 1985 and 1986 we booked small profits, and although our volume was increasing, our expenses were increasing faster. In 1988 Mass Coastal Seafoods filed for bankruptcy.[5] Although it wasn’t a huge financial hit, we did miss their volume, and it was another indicator of the problems in the fishing industry.

Early Signs of Stress

By the end of 1989 we had booked three consecutive years of operating losses. I had cut costs everywhere possible, and lowered my salary and my partner’s. Health care insurance premiums had increased by 30% and, to be fair to our employees, we had increased factory wages by 5%. It was a struggle to cover our payroll and debt expenses while maintaining cash to fund daily operations, and my relationship with my partner was showing signs of stress. He did not share my perspective on our use of funds, and things between us got so difficult that we had preliminary talks about me buying him out. It was premature and the discussions broke down, but it wasn’t a happy environment.

Western Avenue pressroom, 1991. ©Randolph C. Carr

The Slow Decline

By 1992 our sales volume had dropped, the banks were telling us not to increase our debt load any further, and we had laid off a full time employee. Somehow we managed to stay profitable. The fisheries were continuing to decline. Business and employment in Gloucester were moving into manufacturing and tourism. The Gloucester Daily Times reported that “the percentage of Gloucester jobs in the fishing industry went from 40% in 1966 to 18% in 1991. Manufacturing made up to a third of industrial employment: 3,100 employees vs, about 1,000 for the fishing industry. The biggest gain was in the service industry, fostered by tourism.”[6]

By the middle of 1993 it was becoming more difficult to get new business. Many large businesses were consolidating their supply chains, reducing the number of vendors, and moving their manufacturing operations offshore. These were the years that saw a hollowing out of the U.S. manufacturing base. Selling was harder. Many businesses simply would not see you. Often there was not even a human in the front lobby, just a telephone connecting to some faceless gatekeeper who would say there was no one available. The days of talking to the receptionist at the front desk and spending time with the print buyer were vanishing.

Building Tension

From the earliest days, my partner had been responsible for hiring and production, while my focus was on sales and finance. As we moved into the mid 1990’s, he seemed to become less engaged in the business. One of his responsibilities was quality control, but we had ongoing issues maintaining consistent products. I realized my partner was not committed to the business. It was frustrating to bring in new work only to have quality problems that would result in a lost client. While I thought the needs of the business came first, I failed to understand that my partner did not share this belief. I often felt that he was somehow trying to sabotage the business.

Carr Printing, Inc.

One afternoon in January 1998 an employee told me an alarming piece of news. He had heard, from a reliable source, that my partner had been negotiating with Fishery Products to set up and run an in-house printing operation for them. This really shocked me and made me angry. I immediately called Fishery Products and requested a meeting to discuss what I had heard. At the meeting they confirmed it was true. I was in a difficult spot, but explained why I thought it was a very bad decision on their part. After a rather tense discussion they agreed, but said that if I wanted to retain their business I would need to give them a substantial discount on the label work. Apparently my partner had also shared confidential cost and pricing information with them, and with this information they felt they could demand a price reduction. I was not really in much of a position to say no, because their volume was such a significant part of our business. I needed to keep them as a customer. So I said yes and ended the meeting by asking them to give me several days to sort out the situation with my partner. They agreed.

As soon as I left the meeting I went to see our local attorney who had done all our work. He told me he could not represent me because he had already advised my partner about the matter, and would have a conflict if he represented me. This was another shock. Fortunately I knew a Boston lawyer who specialized in corporate matters. He quickly put my mind at rest. The next day my partner resigned, and a separation agreement was executed. Within a week I was the sole owner of the company. The renamed Carr Printing, Inc. was much smaller, both in terms of sales volume, and in the number of employees. There was myself, my son, two other employees, plus my father, who worked part time.

The Fisheries

As 1998 got underway, the fisheries were under continuing pressure. The industry had seen fleet reductions in 1992, and the closure of a large portion of the Georges Bank fishing grounds in 1994.[7] In 1995 there were only three fish processing plants left in Gloucester,[8] and the groundfish catch limit was cut by 50%.[9] By 1997 the daily cod limit had been set to 1,000 pounds per day.[10] Even though the local packers had never been our largest clients, their problems reflected the fishing industry as a whole.

Processors like Fishery Products were also feeling the effects of global overfishing and declining stocks. To keep their operations running they turned to alternative sources of supply. They bought seafood from around the world, using farm raised species like tilapia and pangasius that would have previously been considered undesirable.

During the next few years our business became even more dependent on Fishery Products, Good Harbor Fillet, and several others. Because we had downsized our own operation, it was more difficult for me to be out selling. I became more involved in production. Consequently, our client base became concentrated on a small handful of companies. The fisheries work dominated our sales.

The Printers

By the end of the decade the printing industry was showing the effects of globalization and changing business conditions. U. S. manufacturers had moved operations offshore, and computerization and supply chain consolidations were reducing demand for printing. Total printing industry employment peaked in 1998 at about 828,000. A relentless downward trend began the next year.[11] In Gloucester, Cape Ann Ticket and Label went out of business. They were the first printer in the community to close.

A Difficult Start to a New Millenium

In the early years of our business, expenses were outpacing sales. But now, even with declining volume and price concessions to Fishery Products, we had a smaller payroll and no partner. We were showing profits, reducing debt, and investing in equipment as we started the millennium. The year 2,000 started off with lots of consternation about the Y2K bug that was supposed to crash global computer systems. Nothing much happened and it turned out to be uneventful.

Then came the first recession of the new century. The period between 2000 and 2003 was marked by increased unemployment, decreased business activity, and the terrorist attacks of Sept 11, 2001. It was a difficult time, and our business struggled along with most others. Our sales were down by 25% and we laid off one employee. By the end of 2003 we had booked two consecutive years of losses. In 2005 we wrote off a significant bad debt from Good Harbor Fillet. They had been contending with the same problems as everyone else and eventually were acquired by another company.

Western Avenue pressroom, 2006. ©Randolph C. Carr

Four Color Process

In 2002, Fishery Products expanded their product offerings and began to purchase “4 color process” labels from us. This meant we needed to buy more expensive presses, and more precise platemaking equipment. We purchased the first press in 2002, and a second one in 2006. These were significant capital expenditures that took substantial investments. But we really had little choice if we wanted to remain in business. Fishery Products and four other fisheries companies gave us about 75% of our total sales volume.

The only good thing about this situation was that we were profitable. By 2007 we were running very lean... just one employee, my son, my father and myself. We increased our pricing for labels. Coupled with the reduced payroll and expenses, we had several years of decent profits and paid off all the loans.

The Global Financial Crisis

In early 2007 the world experienced “the most severe worldwide economic crisis since the Great Depression”.[12] This affected us just like everyone else. Our volume declined further. We laid off our remaining employee, and my father retired. Elsewhere in Gloucester, The Pressroom went out of business. This left Carr Printing, Cricket Press, and Chisholm & Hunt remaining.

Fishery Products Sold

In August 2007, Fishery Products was split up and sold to High Liner Seafoods and Ocean Choice International, both of Halifax, Nova Scotia. The fate of the Danvers plant was uncertain. The Toronto Star reported that...“High Liner chief executive Henry Demone said he’s going to review the fate of two secondary processing plants the firm will own in New England. The FPI factory in Danvers, Mass., and the existing High Liner plant in Portsmouth, N.H., have been operating below capacity and are located close to one another, Demone noted”.[13] Several years later the Danvers plant was closed.

Still Printing

By 2011 our volume was so low that it was no longer profitable to maintain our production facilities. My son left the business and moved on to other ventures. I sold our building and equipment. Sometime around 2014 Chisholm & Hunt closed their doors. In 2018 Cricket Press sold all their assets and transferred their client list to Calendar Press in Peabody, Massachusetts. Six months later, Calendar Press also went out of business. By the middle of 2023 total employment in the U. S. printing industry was under 400,000... half of what it had been at its peak in 1988.[14] Gloucester no longer has any sheetfed offset printing facilities. There are only two silk screeners and a couple of sign & graphics providers left in the city.

Even though there have been major changes in printing and the fisheries, I still provide print services for my remaining clients, and labels are still one of the main products I provide. It’s just that they no longer go on boxes of fish. Instead, they go on parts for semiconductor equipment manufactured by the Varian division of Applied Materials in Gloucester.

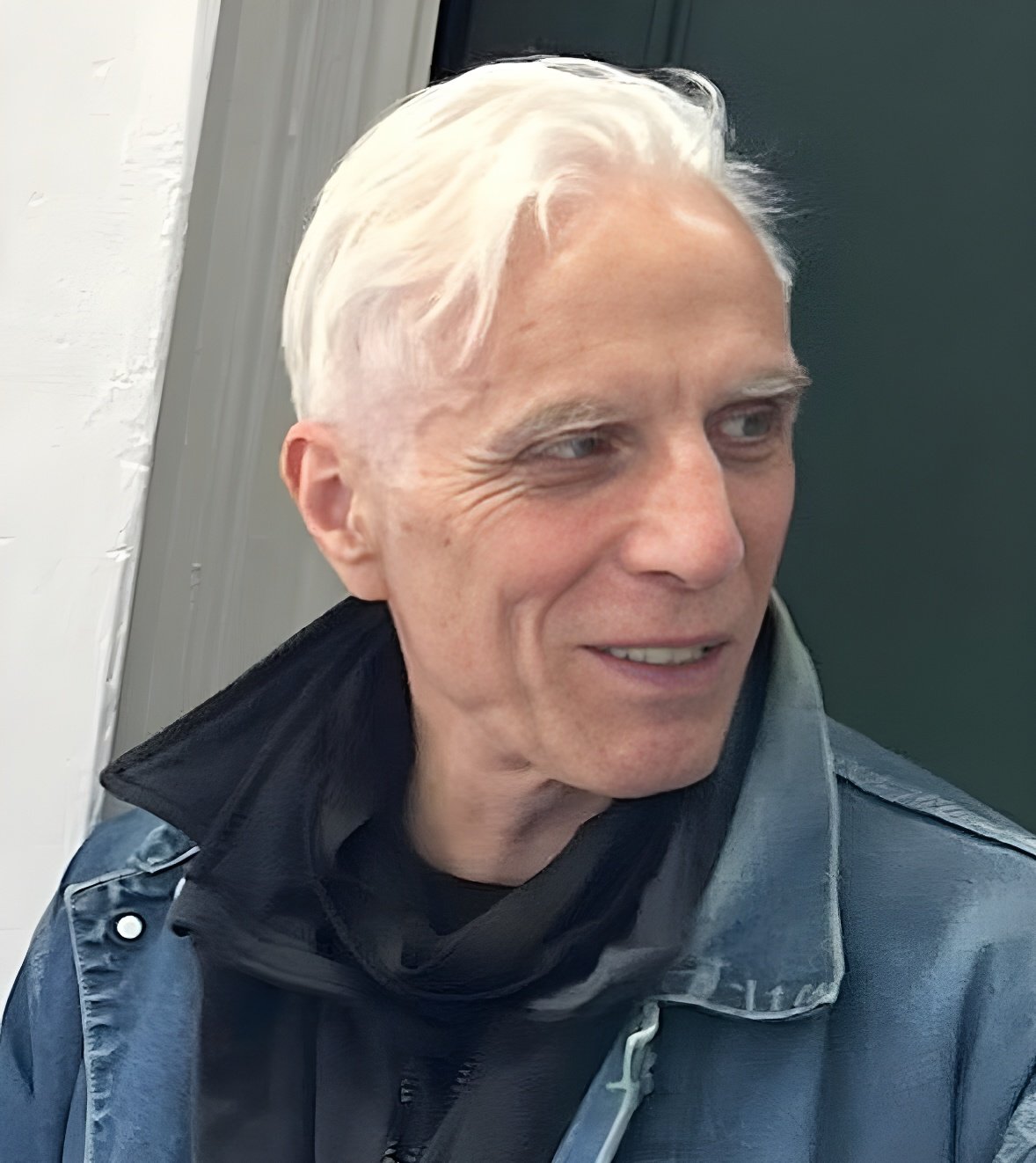

Cape Ann COSMOS will host a reception to honor Randy Carr’s achievement in the printing industry. Meet Randy and see a display of printed samples and a collection of technical devices required for precision printing. Friday April 18, 5pm-7pm. COSMOS Gallery, 20 Pleasant Street, Gloucester.

Randy Carr has been in the printing industry for over 50 years. For an unabridged copy of this monograph contact randy@carrprintinginc.com.

References

1. https://timeline.sawyerfreelibrary.org/timeline/gloucester-fish-landings-reach-202-million-pounds-valued-at-36-million (retrieved 05-11-2024).

2. https://www.intrafish.com/news/how-john-risley-took-control-of-fpi/1-1-751935 (retrieved 05-11-2024).

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clarence_Birdseye (retrieved 05-11-2024).

4. Curhan Printing, Ltd., Corporate Minutes, March 12, 1985.

5. Curhan Printing, Ltd., Corporate Minutes, March 8, 1988.

6. https://timeline.sawyerfreelibrary.org/timeline/employment-in-the-fishing-industry-dropped-by-55-since-1966 (retrieved 05-13-2024).

7. https://timeline.sawyerfreelibrary.org/timeline/the-new-england-fishery-management-council-announced-measures-to-reduce-the-fishing-fleet (retrieved 05-15-2024).

8. https://timeline.sawyerfreelibrary.org/timeline/five-thousand-miles-of-georges-bank-were-closed-to-fishing-and-only-three-fish-processing-plants-were-left-in-gloucester (retrieved 05-15-2024).

9. https://timeline.sawyerfreelibrary.org/timeline/government-regulations-passed-and-groundfish-catch-was-cut-by-50-purse-seiners-quotas-for-bluefins-were-cut-by-20 (retrieved 05-15-2024).

10. https://timeline.sawyerfreelibrary.org/timeline/a-federal-panel-ruled-that-the-cod-catch-was-limited-to-1000-pounds-per-day (retrieved 05-15-2024).

11. https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag323.htm#workforce (retrieved 05-14-2024).

12. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2007–2008_financial_crisis (retrieved 05-16-2024).

13. https://www.thestar.com/business/fpi-sold-to-high-liner-ocean-choice/article_96369450-22c4-5afb-a667-9bba2fab9dec.html (retrieved 05-14-2024).

14. https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag323.htm#workforce (retrieved 05-16-2024).

Who’s Ed Sanders? Unfortunately, at age 85, after an extraordinary career, he remains under the radar for most people. As he sings with his band The Fugs in a recent song, ‘The Fugs will never …