Not Fade Away

Evanescence of Star Betelgeuse

By Paul Erickson, COSMOS Science Contributor

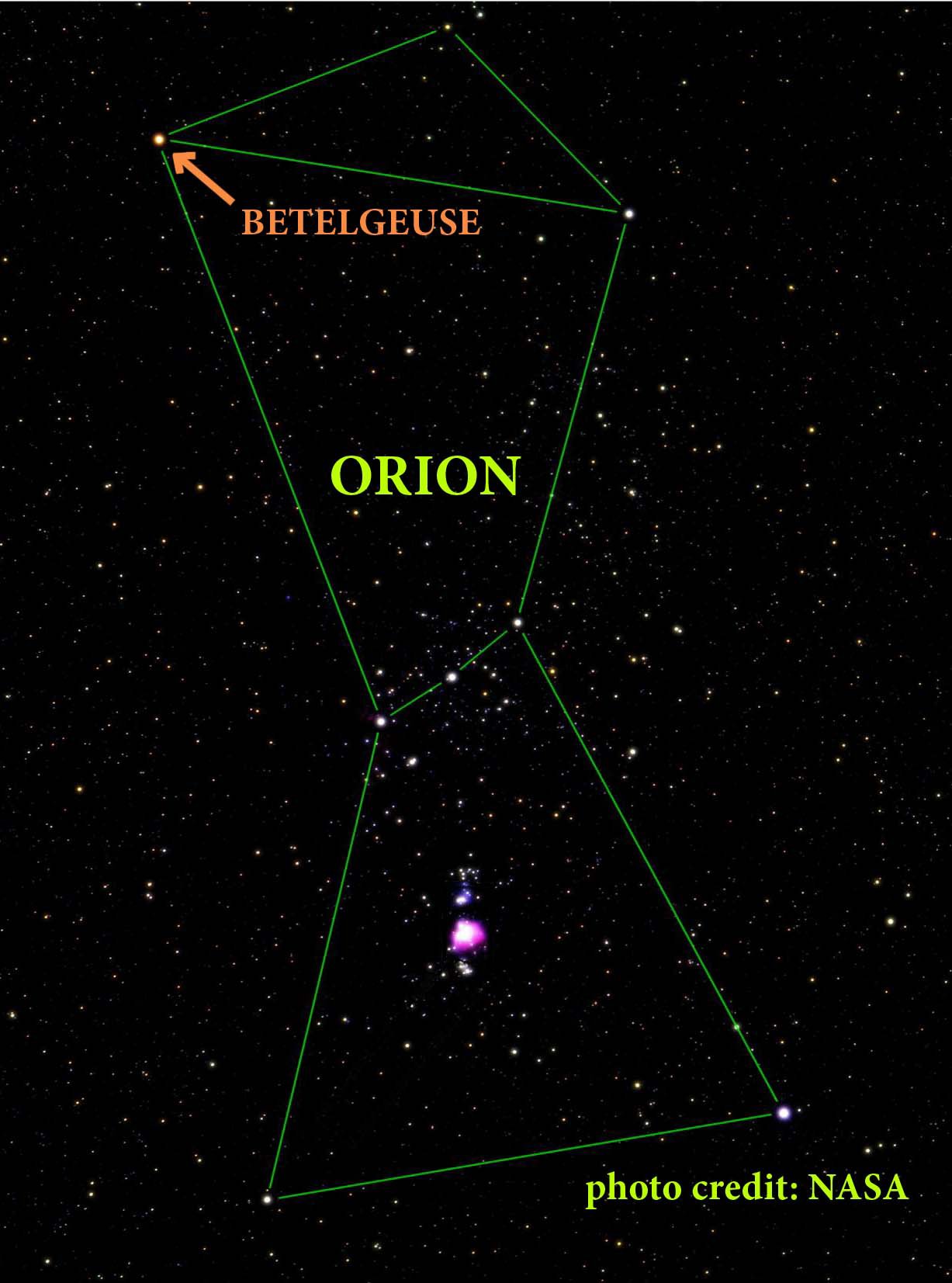

On a bitterly cold winter night back in 2020, I walked outside to see someone I’ve always looked up to. He’s the hunter of Greek mythology—Orion. One of the most recognizable constellations in our night sky, visible in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, Orion fascinates amateur astronomers for at least three reasons:

One, Orion’s belt is an eye-catching lineup of three stars from which hangs the hunter’s sword.

Two, the center object in the sword is a Nebula M42—a star nursery of dust and gas, visible to the naked eye as a tiny fuzz ball. (Actually immense, M42 spans 10 light years or about 34.8 trillion miles.)

Three, Orion displays two of the ten brightest stars in the Northern Hemisphere’s night sky. They are Rigel and the distinctly reddish orange Betelgeuse. If Betelgeuse, which is at least 55,000 times brighter than our sun, were positioned where the sun is, the red-giant star’s surface would be located somewhere beyond Jupiter.

Back to my winter of 2020 night of stargazing, I noticed some high strangeness: Instead of shining like it’s old dazzling self, Betelgeuse looked dim.

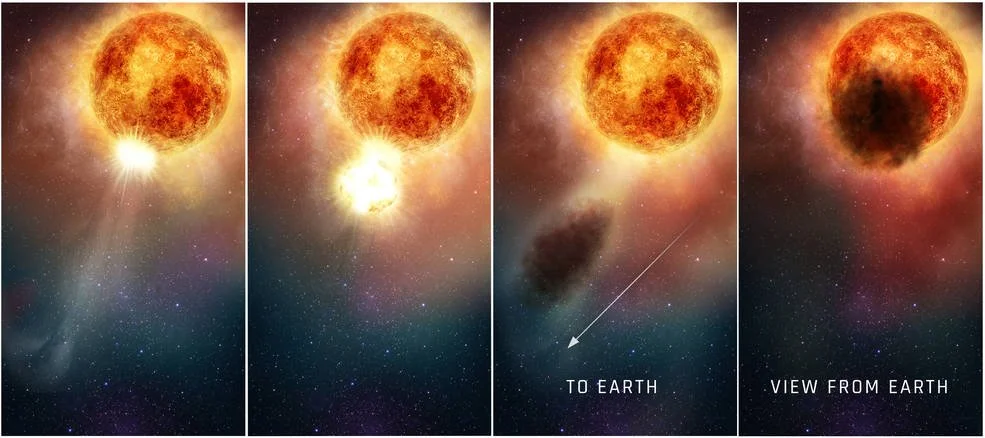

Retreating back into the warmth of my home and the screen of my computer, I searched for any news about the apparently lackluster red giant. According to The Astrophysics Journal (August 13, 2020), Betelgeuse had lost as much as two-thirds of its brightness. The journal article went on to say that during the fall of 2019, the star’s surface released a hot cloud of gas far out into space. As the gas cooled, it formed a dust cloud dense enough to obscure our view of this stellar red diamond.

Some sky watchers thought the fading of Betelgeuse was a sign that it might soon explode as a supernova. That was not likely— historical records prove the star’s brightness is variable. It is unlikely to go ballistic any time soon. Although, if humans still exist in 100,000 years, at some unknown future date, people will probably see the Betelgeuse supernova, which will be visible both night and day for a few weeks.

Although we are talking in the present tense here, bear in mind that if you look up (or out) at Betelgeuse tonight, you are seeing light that left the star about 725 years ago (it’s about 725 light years from earth). So, astonishingly, you’re seeing back in time to roughly the year 1300.

All of which brings us to the Gloucester Area Astronomy Club. The club’s website says this is a “lightly organized group” providing stargazing activities and fascinating public lectures. Group members provide the telescopes. You can contact the group at: gaac.us

Having spent many nights sky watching from Halibut Point and Lane’s Cove ever since I was a little kid, I think you’ll agree that Cape Ann—notably areas away from artificial lights—is an excellent location for amateur astronomers.

The 4-part graphic illustration above shows a hot blob of plasma being emitted from Betelgeuse (left to right, panels 1 and 2). Panel 3 shows ejected gases cooling and forming a vast cloud of dust grains. Panel 4 shows the dust cloud obscuring our view of the red giant from our earthly point of view.

Did You Know?

Galileo’s astronomical records do not mention of the Orion Nebula M42. Why? Perhaps he assumed that the fuzzy nebula was just another air bubble in the hand-ground lenses of his telescope.

We owe much to red giants like Betelgeuse. They form elements such as carbon and iron. When they explode, they produce elements heavier than iron, such as gold.

The most recent visible supernova in our galaxy, the Milky Way, was observed in 1604. People could see this supernova with the naked eye—both night and day—for some three weeks. Because the German astronomer Johannes Kepler carefully documented this exploding star, it is still often referred to as Kepler’s Star.

Spelling bee alert! The correct spelling of the star Betelgeuse is not to be confused with Tim Burton’s 1988 movie Beetlejuice or the cover band Beatlejuice, which featured the late Brad Delp of the band Boston.

Photo credit: NASA